Wearing virtual-reality goggles in near-darkness, they look up, reach out, marvel, then drop to their hands and knees and crawl.

“I’m trying to move in a cavity that’s really narrow,” exclaims one man on all fours, despite the fact that he is on the carpeted floor of a 150 square meter (1,600 square foot) room with tall ceilings. “It’s very small. It’s very cramped!”

“There is almost a sensory experience, although we’re in a space with no sensations,” a woman observes.

“We still have this information in our brain that tells us, ‘Watch out; there’s a wall,’” a second man says. “But, as the experience goes on, you get used to it; you don’t question it anymore, and you admire it all.”

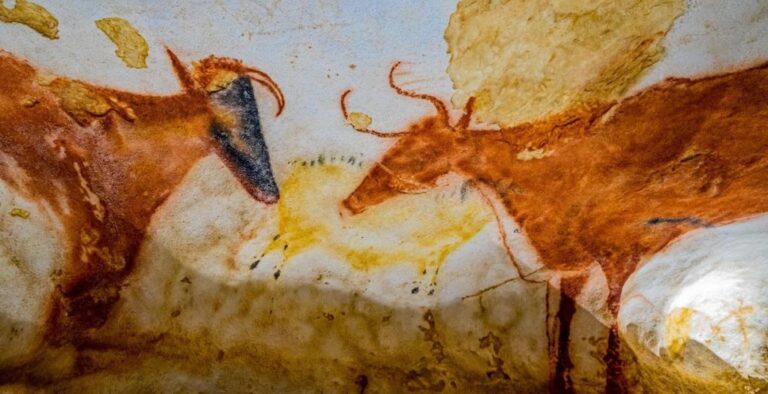

“It” is a life-sized virtual reality (VR) experience of Lascaux Cave, a Paleolithic treasure near Montignac, France, that has been closed to the public since 1963. Following the cave’s discovery in 1940, more than 15 years of daily foot traffic and exposure to human respiration, electric lights and outside air threatened to destroy its 1,900 paintings and etchings, created 18,000 to 20,000 years ago and collectively described as “the Sistine Chapel of prehistoric times.”

For its own protection, officials of La Direction régionale des affaires culturelle Nouvelle-Aquitaine (the New Aquitaine Regional Directorate of Cultural Affairs), part of the French Ministère de la Culture (Ministry of Culture), keep the 235-meter (770-foot) cave network closed to the public. The prohibitions are almost absolute, limiting even preservationists and researchers to a total of 200 hours per year in the cave, for brief visits of no more than two people at a time.

Restricting access helped to save the cave paintings, but limited in-person research and real-time collaboration among larger groups of scientists and researchers. Now, however, a virtual reality tour of Lascaux Cave offers a new way to experience all of Lascaux’s twists, turns and cramped spaces as if you were there, without any risk to the cave or its visitors.

Returning to the cave, virtually

In the decades since the cave closed, experts with the French government developed a series of strategies for exposing the world to Lascaux’s treasures – without exposing those treasures to the world.

Lascaux II opened in 1982. This physical reconstruction of the cave is located on the hill of Lascaux, only a few hundred meters from the cave itself. In 2012, sections of the cave not reproduced in Lascaux II were presented to the public in facsimiles; the global tour of that exhibition is known as Lascaux III. Since December 2016, a nearly complete facsimile of the cave, plus various multimedia tools about Lascaux, have been available in the Centre International de l’Art Parietal, known as Lascaux IV.

In 2013, at about the same time that Lascaux III began its tour, the cave was digitally scanned in 3D. Recently, officials shared the scans with Dassault Systèmes, which develops 3D computer software for use in business and industry and has applied its technology to many archaeological and cultural heritage projects. These include 3D “virtual twins” – scientifically accurate computer simulations – of the Great Pyramid of Khufu; the complete Giza plain; Paris from the Iron Age to the 19th century; and a 3D virtualization of how Allied forces constructed a temporary port for disembarking troops and supplies following the Normandy invasion in World War II.

“We have always used cultural projects to see how we can manage innovation, and to get our engineers to ask new questions,” said Mehdi Tayoubi, Dassault Systèmes’ vice president of innovation. “Talking to new people – archaeologists, historians, artists – and creating fresh experiences is a fruitful way to drive innovation and unconventional collaborations that raise new kinds of questions.”

First-of-a-kind VR technology

Converting the 3D scans of Lascaux Cave into an immersive experience was an opportunity for Dassault Systèmes to help Ministére de la culture “reopen” it to the public, but also to test and refine a prototype VR software kit the company had developed. The kit allows non-expert users to create their own 3D VR simulations from simple building blocks. Importantly for the Lascaux Cave experience, the kit uses avatars to represent multiple users, allowing each person in a group to know where their colleagues are while immersed. This awareness allows visitors to the virtual cave to move freely without bumping into one another or the walls, despite goggles that prevent them from seeing their real-life surroundings.

The experience, currently housed in a room at the Cite de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine (City of Architecture and Heritage) near the Eiffel Tower, employs an OptiTrack camera system to monitor each participant’s position in relation to their peers. Inside their VR goggles, each participant sees not only the cave, but avatars of the other six people in each group, plus a guide.

In developing the experience, Tayoubi’s team discovered that the technology works best when operated by a guide, who can answer questions in real time and highlight specific images just by pointing a finger at them. To see distant images in more detail, the guide touches a control panel to “lift” a group toward a ceiling or move them closer to a wall.

Because the experience is virtual, guides can safely take their tour groups to areas of the cave in virtual reality that have never been accessible to the public – even when the cave itself was open to visitors.

“We have two sections that have not been seen (by the public) before,” said Muriel Mauriac, the cave’s lead conservator with DRAC Nouvelle-Aquitaine. “No one could access them because you needed to find your way through very narrow passages.”

A bounty for researchers

For researchers, the VR experience is – in some ways – better than the real thing.

“Indeed, when you go into the cave you can’t take the time that you take here,” Mauriac said. “You can come as close as possible to the engravings. In the cave we are sometimes 5-6 meters (16-20 feet) away from a vault; here you can really be in direct contact with the walls and with the works and see some incredible details of workmanship.”

“It enables multiple visits to the cave, and you can have 3, 4, 5 colleagues – even more – which you can’t do in the real cave.”

Jean-Christophe Portais, heritage engineer, DRAC Nouvelle-Aquitaine

Because the VR experience also allows multiple people to interact while immersed, it enhances collaboration for researchers and conservators.

“It’s amazing,” said Jean-Christophe Portais, DRAC’s heritage engineer for Conservation régionale des monuments historiques (regional conservation of historical monuments). “It enables multiple visits to the cave, and you can have 3, 4, 5 colleagues – even more – which you can’t do in the real cave.”

The ability to collaborate with others during the experience is invaluable, said Delphine Lacanette, a researcher and teacher with Bordeaux INP, France’s National School of Electronics, Computers, Telecommunications, Mathematics and Mechanics. “For those of us who study the cave, we can talk to each other and discuss the work while it is in progress,” she said. “It’s really very rewarding and complementary” to researchers’ brief visits inside the actual cave.

Learn more about how Dassault Systèmes is reconstructing global heritage sites in 3D

Watch more history in 3D: