My first day at DELMIA Quintiq and my desk looks quite empty. A few notepads, pens, a folder with onboarding materials and – what is this? – a book titled “The Goal”. A novel? I certainly did not expect a novel to be part of the recommended reading. Still, it must be on my desk for a reason. So I take the book home and this is how I “meet” Alex Rogo who is about to teach me a lesson or two.

Alex is the manager of a struggling production plant. His factory has weeks’ worth of incomplete orders, tons of work-in-progress inventories and is consistently losing money. He is given 3 months to turn this poor performance around and to save the plant from closing. 90 days later the plant is not only profitable, but also the best performing one in the division. How did Alex perform this miracle?

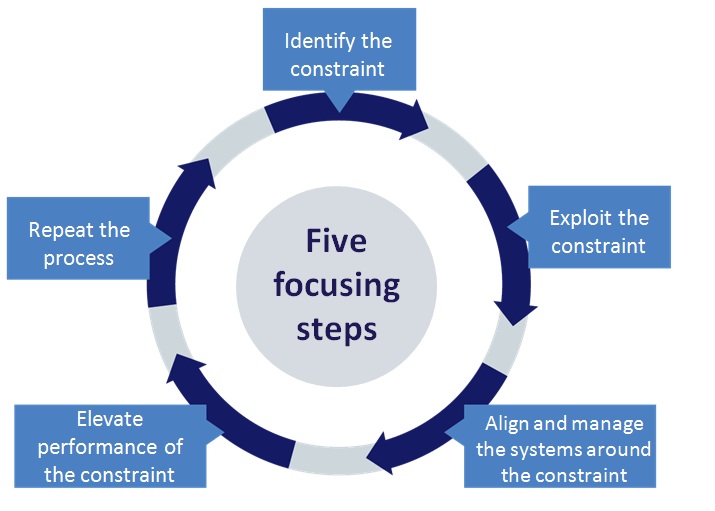

It all starts with the 5 steps described formally as the theory of constraints (TOC). In simple terms, TOC is about identifying the constraint(s) of a system, making full use of it and then subordinating the rest of the system to the flow that goes through the constraint. Once the system flow is smoothed, the constraint’s capacity should be improved in any way possible. Then the process is repeated to continuously improve the system.

At Alex’s plant, the 5 steps look like this:

1. Discover the bottlenecks – the plant’s newest machine (NCX-10) and the heat treat furnace.

2. Exploit the bottlenecks – ensure NCX-10 and the furnace are being used at their maximum capacity. Do so by eliminating idle time (no lunch breaks allowed during set-up times) and reducing the cycle time on the machines.

3. Subordinate the other production processes to the bottleneck(s) – only quality parts should reach the bottlenecks (move augmented reality quality inspection software in front of the NCX-10). Do not let the bottlenecks work on parts that are not needed. Establish a tag system (red and green) to prioritize what the rest of the system should be working on to ensure available parts for the bottlenecks.

4. Elevate the bottlenecks’ performance – dedicate personnel to the two machines, outsource some of the bottleneck work to external suppliers or even run less-efficient old equipment that is capable of performing bottleneck work.

5. Once the bottlenecks are “broken”, repeat the process to find what the new constraint is.

“The Goal” is not just a great reading that uncovers the principles of TOC in a very applied and easy-to-understand way. What really strikes me about the book are the “hidden” lessons I learnt from it and how well they relate to the world of DELMIA Quintiq. More about that in my next blog.

Analogical thinking is key to solving complex puzzles

One weekend Alex is woken up by his son who reminds him that they have to go on an overnight hike with a boy scouts group. To Alex’s surprise, he has to lead the troop during the trek. As the hike begins, he notices that the line of boys is spreading and closing at random. He relates this to statistical fluctuations – in essence, walking at an average pace of 2 miles/hour does not mean walking at a constant rate of 2 miles/hour. The rate fluctuates according to the length and speed of each step. Each boy in the group has a different “fluctuating” pace. What happens is not an averaging out of the fluctuation of their various speeds, but an accumulation of these fluctuations. Throughout the day Alex compares the line of hiking boys to the production plant and notices that the two processes have a lot in common. Finally, he decides to move the slowest boy (the bottleneck) in front of the group and to match the other boys’ speed to the slow kid at the front.

What Alex does during the hike is applying TOC to an event that is practically incomparable to a production process. Thinking analogically allows him to see the production plant puzzle clearly and to make the right decisions in the right order. At DELMIA Quintiq, we experience something similar. Every customer’s planning puzzle is unique. Simply copy-pasting a solution that we already built for one similar customer won’t necessarily work perfectly for another. However, we often draw on experience learned from puzzles that have more in common, even if the industry is different.

For example, passengers going through airport security is a process that resembles a production line at a factory. These are two completely different industries but they share some common planning challenges. DELMIA Quintiq solves planning puzzles in a variety of sectors – from aviation, through intermodal logistics and manufacturing to mining and oil and gas exploration. This allows us to look for analogies across industries, take the best practice from a similar process and create a unique planning solution for each customer.

Key Takeaway: Look for an analogy outside your planning universe. The right answer is not necessarily hidden in what your closest competitors do. The next time you are looking for a smart planning solution, do not stop at the references from your own industry – you may find a much better answer elsewhere.

What does the production of premium textiles have in common with slab casting for heavy metal plates? Find the analogy for our customers Vlisco and Ruukki.

To uncover more hidden lessons from “The Goal”, read part 2 of this blog series.

Reference: Goldratt E., Cox, J. (2010), The Goal: Third Edition, Gower Publishing: Burlington, USA