Cities are hot. And they’re getting hotter.

As we carry out new construction projects or erect entirely new cities, though, it’s possible to design them in a way that mitigates the impact of urban heat island.

Identifying the dangers of higher temperatures, often stemming from climate change, hasn’t been challenging. More reliance on heat-producing infrastructure, increased energy consumption and a growing release of carbon emissions that warm the atmosphere: it’s all there. But there’s potential to design buildings, neighborhoods and entire cities to mitigate the effects of this heat.

What causes the urban heat island effect?

Cities suffer from urban heat island effect, which makes micro-locales significantly warmer than their immediate surroundings. Thanks to high concentrations of vehicles and mass transit, a high density of carbon-emitting office and apartment buildings and a variety of other factors, cities are perhaps hit hardest by increasing heat waves.

To battle the higher temperatures of the steamier months — and years to come — let’s take a look at how cities can embrace urban sustainability to beat the heat.

Heat island causes: It begins with buildings

Cities tend to be centers of construction. From high-rises to office buildings to community centers, there’s always something being built. The problem with this — aside from the emissions from the construction industry — is that buildings produce significant amounts of heat. They’re outfitted with extensive HVAC systems that generate large amounts of electricity, which in turn burn a large amount of fossil fuels.

One effort to encourage construction of more sustainable buildings has been LEED certification. To be LEED certified, buildings must be constructed with attention paid to water use and conservation, sustainable materials and protection of biodiversity, among other factors. The LEED program extends beyond singular buildings, and can be applied to entire neighborhoods within cities. However, it’s just one tool that can be used to ensure some level of urban sustainability.

“It’s interesting to note that some of the hottest cities in the world have always known about the different measures to cool down the heat in urban areas,” said Estefania Tapias, a business consultant in Dassault Systèmes’ Cities and Public Services Industry. “Singapore encourages ‘green walls’ on buildings and has become a leader in their implementation. New York has encouraged roofs to be painted white to increase the reflectivity of buildings, thus reducing heat. Stuttgart has converted a number of streets into ventilation corridors by creating wide, tree-flanked arterial roads that help air flow down from the hills to cool the city.”

This type of informed architecture enables the creation of buildings that make use of existing natural air flows in the immediate surrounding environment. Doing so encourages cross-ventilation and decreases reliance on air conditioning systems, thus reducing the carbon output and higher temperatures that such systems produce.

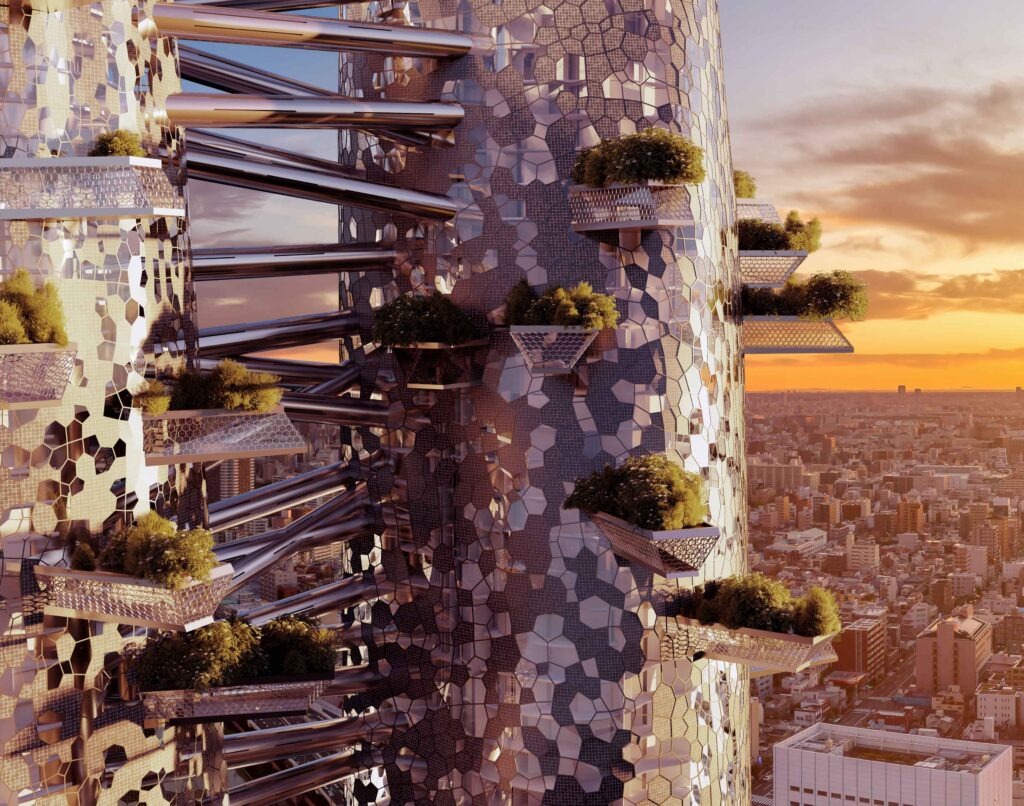

Building facades an also make a significant difference in a building’s ability to regulate heat. Smart Panel, a start-up in the 3DEXPERIENCE Lab accelerator program, designs an outer “skin” for buildings that cools them naturally. Using bio-mimicry and taking influence from human skin — which is remarkably effective in regulating temperature — the company’s environmentally conscious cooling system is a hallmark for future construction.

The dangers of heat pollution: Transportation edition

Creating a sustainable urban environment rests heavily on how and what mobility and transportation options a city has to offer. While buildings contribute markedly to a city’s heat output, so too do the various modes of gas-powered transportation used every day.

“Cars emit heat, therefore the more cars you have on the road, the more a city is going to heat up,” said Tapias.

To solve this issue, some cities have implemented pedestrian-only streets, either for temporary periods of time, or completely. Burlington, Vermont, for example, retains Church Street, the city’s main shopping thoroughfare, as a pedestrian-only area, whereas Boston’s Newbury Street becomes car-less for summer Sundays. Across Europe, the implementation of Low Emission Zones are codifying this concept of reducing cars on the road.

Choosing public transportation over individual cars, or even opting for electric- or man-powered modes of transport, like e-bikes or scooters, can cut down on heat and fossil fuel output. Favoring shared and alternative transit options, like bikes and buses, can help cities reduce heat emissions. Exploring climate change-friendly ways to make these options even more sustainable can contribute even more to encouraging urban sustainability. Dassault Systèmes customer Irizar, for example, designs buses and coaches that reduce less CO2 than traditional options.

However utopic it all sounds, though, re-jigging transportation and mobility systems in cities is an extremely complicated, time-consuming and costly effort to take on. Planners must take into account how to reduce congestion, prioritize bike lanes, expand public transportation options and schedules, all the while keeping commuters and residents happy. To streamline this work, virtual twins provide a simplified environment for considering all the effects and consequences these shifts can have. By compiling them into a singular platform, policy planners, construction companies, developers and more can access a realistic setting for how heat-reducing transportation measures would actually play out for a city.

It all comes down to prioritization. Shifts in transportation trends can have a massive effect on controlling city temperatures, but it’s on leaders to determine how these changes happen.

“Governments need to focus not only on adapting urban settlements, but also in mitigating the effects to prevent temperatures from reaching unlivable levels,” Tapias explained.

That means prioritizing taking measures that support a city’s particular goals when it comes to promoting urban sustainability and heat reduction. For some locales, that might mean decreasing the number of vehicles allowed on the road, whereas for others, it might mean introducing new transportation options that align with those goals. By prioritizing working with companies like Irizar and others with similar missions, and considering the variety of ways to make transportation more sustainable, cities can take a multi-pronged approach to cooling off urban areas.

The living environment’s impact on urban heat islands

Greenifying cities offers an opportunity to revolutionize urban surfaces and landscapes.

Planting trees, simple as it may sound, is an important tool in cooling off cities and fighting climate change. It’s well-documented that wealthier neighborhoods tend to have more trees and green spaces than poorer areas, contributing to significant differences in temperature within urban areas. By providing shade, trees cool their surroundings, reducing the need for air conditioning and cooling off surfaces like pavement sidewalks, parking lots, and streets. They also absorb carbon dioxide, making them a net-positive tool for improving air quality.

In addition to planting trees, using fabric covers for communal areas like playgrounds also provides a shield from heat. Consider that different materials absorb heat differently, and the equipment often found on playgrounds can reach unsafe temperatures for children – or anyone. Creating artificial shade works twofold: it encourages residents to get out of the house (and out of the air conditioning) and does so by making sure community spaces are heat-safe.

What’s at stake with urban heating

Cities are experiencing a boom. Worldwide, more than half the global population calls a city their home, and this trend is only set to increase, according to predictions by the World Bank. With more people comes the need for more buildings, more transportation, more cooling systems and, eventually, more heat.

“The cities of the future will be warmer, despite efforts to reduce heat islands,” Tapias said. “The fundamental problem remains global. If cities reach very high temperatures in the future, we need to rethink how these urban spaces function.”

Dassault Systèmes’ The Only Progress is Human campaign features a project centered on issues just like these. The Act for Cities and Urban Sustainability outlines the need for transformation in mobility services within cities as a part of improved planning. The Virtual Twin Experience in Infrastructure and Cities encapsulates the various factors that go into designing sustainable cities. The system enables virtual ideation and design for urban sustainability solutions that deal with waste reduction and management, water quality management, resilient building creation, sustainable construction supply chain methods and beyond.

What’s the economic impact of the urban heat island effect?

While urban heat islands are physically uncomfortable for residents, they can also be fiscally uncomfortable, too. The cost of hotter cities is significant.

Hospitals experience increased numbers of patients sick with heat-related illnesses. Wealthy residents may flee cities for cooler locales, taking with them significant financial resources that urban areas depend on. People of all socio-economic classes might make similar moves to cities with more temperate climates to begin with, driving up rental costs in these new cities. When these individuals leave their hot cities, they may also leave their jobs, which contributes to a decrease in economic productivity.

What’s stopping us from cooling off cities?

The problems stemming from urban heat island effect have been well-documented and their solutions identified and verified. And yet, progress to reduce their prevalence is slow.

“In my opinion, there are two factors that stand, or may stand, in the way,” of implementing heat-reducing changes, Tapias said. “The first is political.”

Equipping urban leaders with the necessary tools to explore, design and implement changes is the first step. Mapping out a virtual twin of a neighborhood within a city, like with Rennes Métropole, for example, can be a game changer for policy planners to best understand how to create sustainable micro-environments. From where to plant trees to how to create zoning laws to understanding which urban surfaces produce the most heat and do it all in a cost-effective manner, virtual twins enable cities to create sustainable futures.

The second factor, Tapias added, is from the perspective of a city’s residents.

“Even if a city implements certain measures, citizens play a significant role in making them successful. At the end of the day, citizens are the ones who approve, maintain and act on these measures. If they feel they have been heard and involved from the beginning, the probability of them accepting these measures is higher,” she said.

Reducing the negative impacts of urban heat for a sustainable future

Urban sustainability will need to become a key component of city planning if we expect to build a future that works for all the world’s people. Revitalizing cities that work for their residents can be a core goal for policy planners and architects. And it can start small: reducing the prevalence of parking lots in cities, for example, by constructing them underground and changing those asphalt urban surfaces into green oases is a meaningful starting point.

It’s possible to design sustainable cities that can better withstand the increasing heat waves of the future. Designing buildings with lower carbon-intensive materials that reflect light, produce less heat and use less electricity is one important facet of this. Re-thinking roadways and even rules of the road to promote pedestrian, mass transit and alternative transport options will further create a more livable, sustainable urban space. From planting more greenery to exploring solar energy options, the potential for a future of urban sustainability is limitless.